Colorful Local History

A Colorful History Lesson

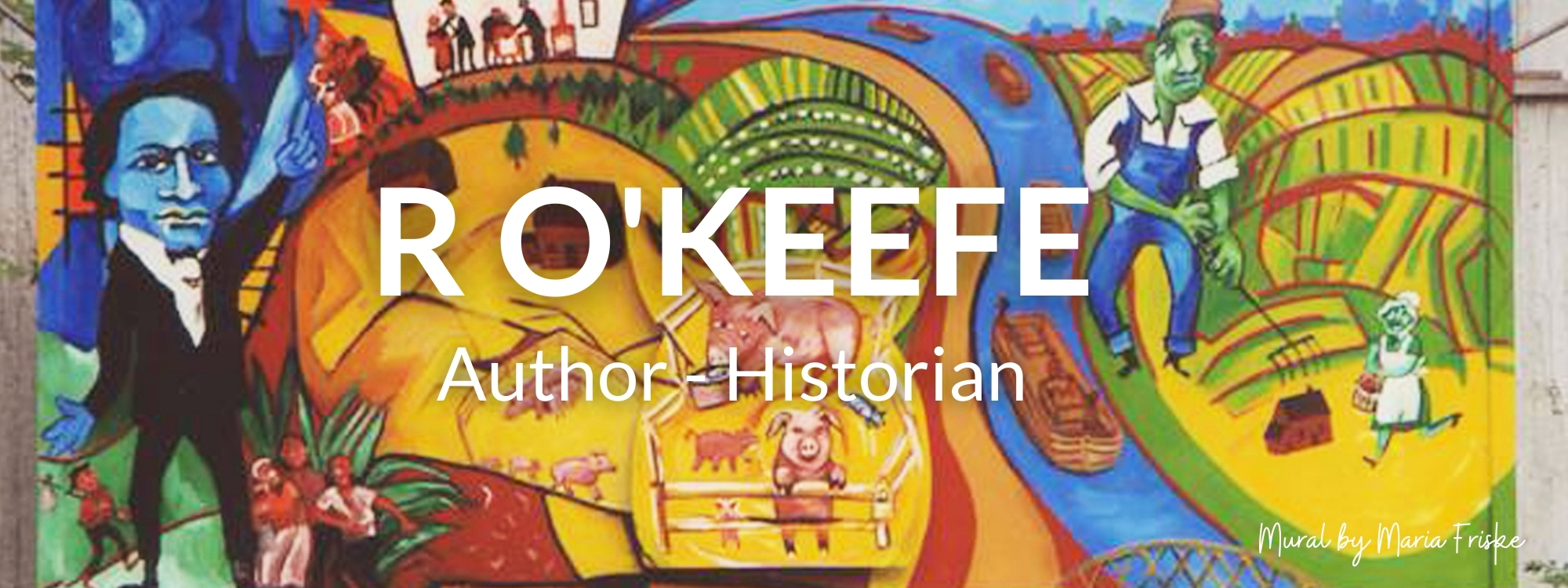

Rochester folk artist Maria Friske is a genius. Her five murals on Pembroke Street offer a marvelous look at the local history that led to the growth of Rochester and the south-east side. Her colors are so vivid, the swirling people, animals, boats and trains are as alive as art can be.

At the unveiling of her public art project in the summer of 2006, this neighbor got goose bumps just looking at the first panel, The Creator’s Garden. Sky Woman, the Seneca’s long houses, the three sisters of corn, beans and squash, and the Finger Lakes are all there.

One reminder of this region’s early is the plaque on a boulder at Cobbs Hill near Highland Avenue that honors the Portage Trail. It was part of the Ohio Trail, which northeastern Indians traveled on from Canada into the Mississippi Valley. Another is the marker at the University of Rochester, for the primitive Algonkin village of nine acres with tilled fields that flourished by the Genesee River about 800 years ago.

This writer once got a lesson about Northeast American forest dwellers while on a family trip to Ste. Marie-among-the Hurons, near Georgian Bay. In a matter of decades, almost 250,00 Indians – more than the population of Rochester – were wiped out by diseases they didn’t have names for. Even though the Mohawks in central New York were hit by a smallpox epidemic in 1615, the Iroquois League of the Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, Onondaga and Senecas reached its peak population around 1750. Their lands stretched from Canada to the Ohio Valley.

It’s a bit harder to find out about the first African-American explorers, frontiersmen and escaped slaves who hid out in today’s Monroe County. They got here, no doubt, along ancient Seneca paths.

The second panel, Always Know Your Neighbor, portrays the Erie Canal, Frederick Douglass, the Underground Railroad and pig farms. As U.S. immigrant and slave populations grew, pioneers, farmers and businesses wanted a faster route west than the long way south by ship to the Mississippi. The first proposal for a canal from the Hudson River to the Great Lakes was written in 1785 at a time when some of that land was still owned by the Senecas.

The Treaty of Canandaigua of 1794 defined Seneca lands as roughly much of New York west of the Genesee River to Lake Erie and from Lake Ontario to the Pennsylvania line. The treaty was supposed to respect the small number of surviving Indians, but as pressure from land and freedom-hungry settlers grew, more Seneca lands were sold in 1797.

Canal construction began July 4, 1817 in Rome from the Mohawk River to the Seneca River. Starting in 1819, Irishmen pitched their work camps near Comfort Street to work on the Rochester section. They were one-quarter of the immigrants who dug the canal, along with Welsh, German and English workers.

The novelty and speed of the canal seemed miraculous compared to travel by shank’s mare or horse and wagon on rough, muddy roads that had been hacked from native trails. From the beginning, every one used the canal: poor immigrants, wealthy vacationers, workers of all kinds, religious groups and abolitionists hiding slaves on their way to freedom in Canada.

Between 1816 and 1848, about 2,000 slaves passed through western New York’s Freedom Trail as worshipers seeking religious freedom flocked west across the state. From 1815-18, Baptists, Congregationalists, Methodists and Presbyterians who had held 21 revivals in eastern NY, held 80 in the Burned-over District of central New York into Genesee Country.

Before 1820 Rochester was a struggling village of 1,500 between county seats in Canandaigua and Batavia. When the canal crossed through Rochester, no town west of Albany and Troy could rival it in size or growth rate by June 1820. It became a boomtown with a growth rate of 800% from 1818 to 1828.

When the Great Embankment was finished in October 1822, water from the Genesee River flowed east across the Irondequoit Valley; travel time from Rochester to New York City was cut from 42 days to nine days; and westward expansion exploded. The canal helped make New York City a dominant port and opened Great Lake states including Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan to immigrant settlers.

The official opening was celebrated on Oct. 26, 1825, when the Niagara entered the canal from Lake Erie and reached the Hudson River six days later. Ceremonies called The People's Jubilee, took place the whole length.

By the time the 363- mile hand-dug canal was finished from Albany to Buffalo, 2,000 canal boats had used it; Rochester became America's first inland boom town; and farmland in Genesee Country became the nation's granary. From 1828 to 1840, Rochester was the number one boatbuilder in the nation larger than New York City, Boston and Baltimore because of its fine canal boats described as "fairy palaces in miniature." These were built close to downtown.

By the mid-1830s, the narrow canal was choked with traffic. The first enlargement began in 1836 and even though it wasn’t finished until 1862, traffic tripled in the 1840s. It took a few decades for boatyards and sawmills to move eastward from downtown. Maps and ads in the city directories of the 1840s, 50s and 60s give a block-by-block view of this early urban sprawl. The third panel, Always Know Your Pal, shows houses inside a big red pig, schools, an orphanage, and Cab Calloway as a boy.

It’s impossible to miss the large, red pop-out pig in the fourth panel, The Subway. Travelers along the new subway bed that replaced the enlarged canal in the 1920s are surrounded by the downtown skyline, Highland Park Diner, the Cinema and Colgate Divinity School. Many locals remember the subway fondly, including animation-artist Fred Armstrong who created a documentary, The End of the Line – Rochester’s Subway. The subway was replaced in the mid-1950s by the I - 490 Expressway. Each of the colorful panels puts the zip back into local history.

The funky street scene of people, stores and restaurants along South Clinton Avenue on the fifth panel, Currents, has a jaunty, hip feel to it. In the process of writing about southeast Rochester history, this writer has wondered why people are either so opinionated or confused about the boundaries of the Swillburg, South Wedge and Ellwanger & Barry/Highland Park neighborhoods.

An educated guess: World War II and Boomer neighbors defined home by their family parish, grammar or high school, corner stores, local bars and, up until 40 years ago, the old political wards. There’s no arguing with an unshakable definition created by the mind and heart of someone who says, I grew up here and this is what we called it.

There is a logical explanation for the geographically-correct definitions of where Swillburg ends and Highland Park Neighbors or the Wedge begins. Neighborhood associations that were formed in the early 1980s defined the grant areas they served by local census tracts. No contest – people who live and work in a neighborhood don’t have to think like grant writers. Many long-time Swillburgers have strong bonds to the way it used to be. Mostly likely the Senecas felt the same way about the shining valley they called Cheniseo.